A pure coincidence. An opportunity to reflect, again. A virtual line, an explanation to be found in history books discloses the connection between the toponym of a Berlin street in the Wedding district and an art exhibition on the other side of the city, in Neukölln. These two areas share today also similar patterns in terms of urban development and challenges: they both register a high rate of immigrants and naturalized Germans and are experiencing a relatively fast process of gentrification. Maybe a Togostraße, my current domicile, or a so-called „African district“ exists in other European countries. Certainly in those with a past as colonizing powers. Indeed, here another coincidence: in such an area I used to live in Rome as well. Libya, Eritrea and Ethiopia instead of Togo, Namibia or Cameroon but still same dynamics between intruders and locals. With this set of thoughts in mind, on a gloomy and cold Saturday afternoon of end January 2015, I made my way to the Savvy Contemporary e.V., a laboratory of form-ideas which aims at fostering the dialogue between „western art“ and „non-western art“.

On the occasion of the 130th anniversary of the Berlin Congo Conference in 1884-85, the exhibition WIR SIND ALLE BERLINER: 1884-2014 curated by Simon Njami reminisces this historical moment, questions the geopolitical (and social) situation in present days and raises issues concerning the new meaning of colonization, identity and migration. Two centuries ago, due to the Portuguese initiative and under Bismarck’s invitation Western (European, North American and Ottoman) colonial forces officially set the rules to partition the already colonized African continent. By doing so they influenced not only the destiny of Africa as a whole, but this partition affected the initiators as well: the social-cultural geography of Europe changed, and this process is still ongoing. History is not a straight line and each event entails repercussions.

Two floors with powerful works on display, which message goes beyond the closed walls and strikes you in the very deep. As it usually happens, some of the artists affect us the most, their language talk to us in a more effective and direct way than the others, and what follows is a recognition of what I took back home on that cold winter day.

I enter a small room with a video, where a soft hypnotizing voice (French-speaking) guides me through the images showing exhibits from the collection of The Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium, the last remaining colonial museum closed in 2013 for renovation. “Into the Interior (The last day of permanent exhibition)” by Katarina Zdjelar is an aesthetic and anthropological research which by using the same categories of an obsolete cataloging technique, initiates a reflection about historical and cultural narration. It reminds us of a past which is partially influencing the way we describe the world today. Next to it, a small installation on a pedestal and a tiny colorful piece of paper hanging on the wall above it catch my attention. I virtually travel to another continent, leaving the “old world” for the US, where I see porcelain figures on a vibrating snare drum gathered around an Indian-American totem, and meanwhile I learn the “Cowboy’s prayer”. Satch Hoyt with his “How the West Was Won” attempts to narrate another chapter of European colonial history in North America, starting from Columbus and ending up in a Hollywood western movie. I go up the stairs and encounter other challenging works. Cyrill Lachauer‘s installations are a continuation of the theme approached in the previous work about Native-Americans. Faked Sioux rituals, Buffalo Bill’s icon, the legacy of Bartolomeu Dias’ “discovery”, a baseball bat of American Redwood and traditional hunting tools surround “Horses, Manillas and the Smallpox Blankets”, and all together tell stories of exploitation, brutal colonization and reinterpretation of symbols. In “Mémoire”, Sammy Baloji intertwines his biography with the colonial history of his home country, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. His photomontages invite the viewer to rethink the concept of “development”, approach the issue of resources exploitation and the rights of communities to freely dispose of them. A dialogue between two different points in time, an assessment of the current (devastated) situation of the mines once belonging to the Belgian Union Minière du Haut Katanga in Lubumbashi, represent a clear statement on how a gone past affects present daily life. With Nadia Kaabi-Linke I am 100% in today Berlin, I explore the dimension of public art intervention where the focus is laid mostly on the process and on the direct involvement of the target group. “Meinstein” is a project which embodies the DNA of the city and takes a representative snapshot of its inhabitants. A square in Neukölln as metaphor of community life, becomes a place where to reflect about migration, memory, home and origin. People and their heterogeneous life experiences shape the space where they live, and originally not native elements create new interesting always changing syncretism. The main lesson is that culture is a fluid concept and multiculturalism the normality. I move forward and encounter a series of 13 printed ceramic plates hanging on the wall, like a collection of handcrafted souvenirs you could find in your grandma’s house. But the subject-pattern is somehow distressing. Body parts on them, a black body and 13 as symbolical-holy number, like Christ and the Twelve Apostles. Bili Bidjocka in his “Dis-ambiguation (Do Not Take It, Do Not Eat It, This Is Not My Body..)” explores the realms of spirituality and secularism, playing with fundamental assertions of Christianity. Divine and mortal coexist in God’s son, but the Father always remains unseen, absent from the ephemeral world and his essence dissolves in the flesh. Another step into history, a journey through modes of memory production is presented by Filipa César. The video “The Embassy” is a narration that deals with Portuguese colonial presence in Guinea-Bissau. A photo album shows power relations and how European eyes captured and meticulously documented their understanding and perspectives about the occupied country, indirectly creating a mirroring process. An entire room is dedicated to an ambitious utopian project which refers directly to the legacy of the Berlin Conference, the “Laboratoire Déberlinisation” founded in 2001 by Mansour Ciss Kanakassy together with Baruch Gottlieb and Christian Hanussek. A mixed media claim to problematize the artificially drawn borders of the African countries, and at the same time a hope for the African people to be one day entitled to financial and political self-determination. This room talks also about other boundaries, those between art and politics and presents the scenario of them becoming thin and merging into militant engagement.

Past (and recent) history is not something fixed, a given truth. It could be compared to some extent to a kaleidoscope, as what we see changes according to the perspective and the point of view we take on each time. It allows to make parallelism, interconnections among events, places, ideas and people. And I do the same with this exhibition by recalling other “coincidences” which lead me to virtually expand the number of exhibited works dealing with similar topics and to find other pieces of the puzzle in quotations and positions captured during round tables or symposia. I start by going back in time of two years and closing with early March 2015.

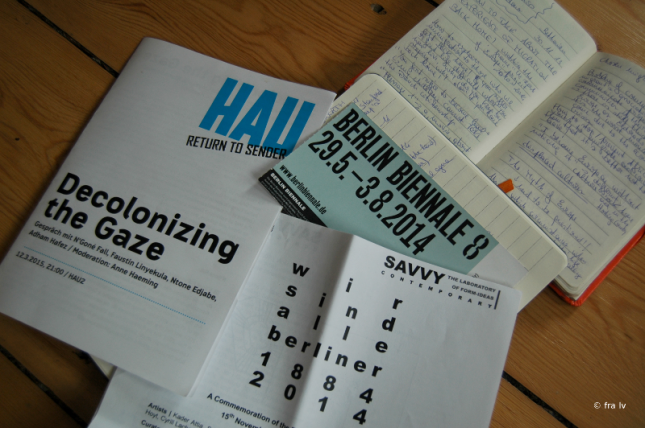

The BERLIN BIENNALE 8 (2014) curated by Juan A. Gaitán, focused on the exploration of the existing intersection between larger historical narratives and individuals’ lives. Therefore, among the presented artistic perspectives some works approach exactly the chapter of colonialism. Cynthia Gutierrez for example with her “Diálogo Entre Naciones“ carves two veiled marble busts of Benito Mussolini and Heile Salassie and places them one in front of each other. Their equal position on the plinths reverses somehow their role in history, and the hidden line of their mouths stands as metaphor of the relations between colonial forces and occupied countries. History in this case had a partial revenge, as the Obelisk of Axum stolen by Italy in 1937 as symbol of the „new Roman empire“ was returned to Ethiopia in 2005 (although it was agreed to execute the repatriation already in 1947). Carla Zaccagnini’s installation “Le Quintor des Nègres, encore” in cooperation with composer Theodor Köhler, the Aulos-Streichquartett Berlin, choreographer Ayara Hernández Holz and performer Felix Marchand, is a provocative reference to the paradoxical connection between Romanticism and colonialism, between art, philosophy and politics. A carbon copy of the score of Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Quintuor des Nègres (1809) from the ballet “Paul and Virginie“ based on Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s Rousseaunian novel with the same title, is on display with several editions of the novel in different languages (German, English, French, Spanish, Datch and Italian) dating back 1882-1900. The aria plays again in the elegant and exclusive hall of Haus am Waldsee in Berlin facing the adjacent garden and lake and expands through space and time: past and present bourgeois amusement. We move to Australia with Gordon Bennett´s „Notepad Drawings“, where he deals with the unbalanced relation and the persisting, destructive inequalities between Indigenous and white Australians that began with colonisation. Essential lines, studies, rough ideas on paper and colorful naive pictures reproduce with offensive language and scenes from collective imagery this multi-layered attempt to belittle Indigenous peoples. Finally, Bianca Baldi in her „Zero Latitude“ brings us back to Europe and Africa, by exploring yet another aspect of not immediate connection where the world of fashion attends upon colonialist needs. The protagonist in this case is an object, a folding travel bed. Commissioned by Italian aristocrat and French naturalized Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza who used it during his explorations of central Africa, the bed „Explorator“ was custom-made in 1870 by the later luxury haute couture brand Luis-Vitton. Brazza was praised seven years later by the Royal Geographical Society in London for the outstanding geographical documentation ever done in Africa, and the capital of the Republic of the Congo was named Brazaville after him. The video is a metonymy reminiscing a commercial, where a white-gloved butler shows from different angles how to open the suitcase that contains the object and make the bed. History can be told also by looking at details, by enlarging the view and positioning objects in a larger context, where final consumers and industries contribute to the establishment of an imperialistic empire as much as governments.

In 2013 I had a first approach with a similar topic through another exhibition in Berlin, this time in the district of Kreuzberg. IN SEARCH OF EUROPE, a group exhibition at Bethanien curated by Daniela Swarowsky in cooperation with six researches from Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) within the frame of a larger 4-year research project, questioned indeed the whole concept of North-South relations of dependency and predominance. Or in plain words of center and periphery. The legacy of colonial expansion and post-colonial dependencies, the new role (and meaning) of Europe in a contemporary plural world, its pull and push factors outside the “fortress” and the way the non-Europeans position and see themselves and how they cope with Western standards. To mention a few of the core issues explored on a multidisciplinary basis, ranging from different artistic expressions to anthropology, from Islamic studies to history and from urban planning to education. “The thing is: for you this is a project, for me are problems, mine!” a quotation as short glimpse into the multimedia installation “Yacine’s Voices” by photographer Charlotte Menin in cooperation with the anthropologist Knut Graw. As many other works exhibited on that occasion, Menin decided to humanize the entire discourse behind the issue of migration and integration by telling a particular story, by tracing a sort of intermittent biography of Yacine who writes poems in French (not his mother tongue) as immigrant and as lonely human being, too. Thus, the installation blends together a social-political portrait of a society and a single cry of a person attempting to make a living within a complex context. In another room, a black and white video mimics the rhetoric of the inauguration day of a USA President. With “My European Mind/Re-branding Europe” the collective Bofa da Cara questions with the format of a pseudo-official speech the given-for-granted European certainty of being the center of the world and invites Europe as a whole, as if it were a living person, to rethink and redefine itself. Identity (re)branding seen both as necessity to accept the other, the non-European, and as survival strategy to face the raising challenges of a globalized world. This is an unusual exhibition. It comprises not only art works in a proper sense, but also reports the timeline of the parallel research, suggests a comprehensive and multidisciplinary bibliography, shows field notes and paper drafts as if they were preparatory sketches for a monumental painting, lays bare doubts and unpolitically correct statements by members of the team and initiates in the viewer a process of self-assessment by adding an extra layer with screenings and panel discussions. Among the latter, “How to talk about the experience of migration back home?” a 2-3 hour open discussion tackled mostly all previously mentioned themes. Under which circumstances, when does exactly this idea of a better life abroad in Europe become so compelling for potential migrants? And how to fill the communication gap between people left in the home country and those experiencing harsh living conditions in a developed European country? How do people cope with displaced cultures? What is the connection between migration and nationalism? And finally, what does “home” stand for? Questions like those were raised and raised likewise new difficult-to-answer questions by looking at the specific situation of African migrants living in a foyer (a guest worker dormitory) located in a Paris suburb, documented by the artist Anissa Michalon in cooperation with the anthropologist Aïssatou Mbodj-Pouye. But this scenario could unfortunately be extended to other receiving countries, to other migrants with different nationalities, to another “rampart” of Europe.

2015. Some of the guest speakers of the previous open discussion in 2013, I recognize two years later among the public gathered for the keynotes lecture at the ICI Berlin by the curator Simon Njami and the anthropologist Ann L. Stoler within the frame of the exhibition WIR SIND ALLE BERLINER: 1884-2014. Again another coincidence? I would rather say a mutual contamination, since the catalog of the Bethanien exhibition was on the shelves of Savvy Contemporary’s library. And more in general I would consider these series of events taking place during the last years as an important sign marking the beginning of a mature era, where the temporal distance and the generational change allow to dissect thorny historical episodes in a tabu-free way. The symposium brings me back and forth between present days and the end of the 19th century. The continuity of history is somehow denied when historical moments and episodes are isolated, and someone decides which are eligible for going under the magnifying glass and being presented to a broader public. This, in the words of Bonaventure Ndikung, is what happened to Savvy Contemporary when they saw their project dismissed and denied financial support by many German funding institutions. Simply the theme of colonialism didn’t meet their funding principles, for their research field is restricted to more recent chapters of the German history, such as the Holocaust and the division/re-unification. Simon Njami centers his analysis on France, more precisely on the cultural and political Parisian milieu from the French Revolution to the 2007 outrageous Dakar´s speech by former French President Sarkozy. A list of echoing quotations and ideas that span from Sartre, Picasso, Conrad, Star Wars and Hugo. A sclerotic dialectic contrast without synthesis between lightness and darkness, white and black man, superiority and inferiority. A justification to exploitation found in eminent words. “The tragedy of Africa is that the African has not fully entered into history [..].They have never really launched themselves into the future” (Sarkozy, 2007) may sounds like “God offered Africa to Europe. Go build houses, build cities, colonize!” (Hugo, 1879). Are there shades of gray in the middle between black and white, some kind of cosmopolitanism? A question form the public that could be interpreted as sort of plea looking for a positive approach. White and black are not colors by definition, but as David Batchelor pointed out in his book “Chromophobia”, there is in the West since Antiquity a manifested attitude to marginalize and degrade colors opposed to the valorization of white as the color of rational, clean and controlled spaces. Gray lies in art! And there are evident proofs. Indeed, modern art comes from Picasso’s shock in front of African masks, black people studied in Europe and in capital cities nationalities have to disappear. Metropolitan spaces build a bridge between lightness and darkness. Who is in the end a Berliner?

Ann L. Stoler glosses even more the discussion and presents the general situation in the academic world and in the popular culture. She warns us from the risk of falling in the “trap” of decolonizing theories seen as an attempt to disregard the colonial history, which to some extent endures still today. She argues that where colonialism acts, we are confronted with an uneven temporality. Recollecting the pieces of world history is therefore a collective task, you cannot find the “truth” in one place, in one interpretation. When facing history you have to deal with discomfort, which no de- project could ever guarantee.

On March 12, 2015, the panel discussion “Decolonizing the Gaze” within the frame of the RETURN TO SENDER Festival at the HAU Berlin, dared to present another challenging perspective on the legacy of the Berlin Conference. What if the emphasis put on this meeting did overestimate its actual scope and the repercussions on the affected African continent? When does the cultural and artistic ferment become the main topic of discussion and analysis, instead of re-perpetuating this dialectic of victims and oppressors? Is this of any good, and for whom? A black and white postcard sent from the former Belgian-Congo and found more than a century later on the Internet by the curator N’Goné Fall serves as trigger to explore not easy to grasp dynamics. Her name creates in my mind a connection with the exhibition visited in January, on that cold Saturday afternoon. Ms. Fall has been indeed co-founder and editor in chief of the art review Revue Noire, together with the curator Simon Njami. So far for the “coincidences” series. On that same stage, next to her chair, a small group of African guests and the German journalist Anne Haeming gathered to discuss about artistic practices and experiences influenced (or not) by the old European paternalistic-colonialist scheme. The public is confronted with a sort of rebellion in terms, where every thought uttered by the journalist Ntone Edjabe, the choreographer Faustin Lynyekula, the dancer Adham Hafez and N’Goné Fall, hits with the heaviness of a hammer a few attempts by the moderator to conduct the discussion at a standardized European and German-logic pace. The main question is of course “whose gaze” needs to be decolonized. The European belief of having discovered a world, the vast African continent, this intellectual and political arrogance is torn down and Africa must be perceived as a non-homogeneous block. How does Africa see herself? Does this issue really matter? Hafez, on purpose dressed in traditional colonial Egyptian clothes, is annoyed by the fact that African artists (and non-European ones in general) are first and foremost addressed and invited to Western countries as representative of an ethnic category more than as simply artists in the broader meaning of the term, just like their European peers. Reality is much more complex than the Eurocentric or bipolar geopolitical approach, it’s not a “quick food” as defined by Lynyekula. And it is argued that language allows space for uncertainty. The Western obsession with facts and data, the need to measure knowledge, immaterial aspects like emotions, thoughts or imagination as necessary information to establish a dialogue with the world, all this is challenged by a single word from the Zulu language: Angazi. “I don’t know, but I’m sure”, a new way to intelligence, the key to understand a series of self-produced maps by Edjabe to “explain” contemporary movements inside Africa. Do they make sense to us? Again the question, what is more important to know exactly or to feel? The answer lies in the “right to opacity” theorized by Edouard Glissant, as an active strategy of resistance against the right to transparency as perpetrated since the colonial era. The right to claim for the power of imagination, the right to simply do art and to be appreciated for that. A tricky point to close the evening, if this whole structure of European funding policies for African artists represents a way to make the guilt go away, to make up to their ancestors. Whom is this question so crucial, Europeans or Africans? What really matters is to create space for artistic expression, to have chances and to use them as much as possible. And if a country is intellectually honest, like Germany in the eyes of Fall, then everyone can profit from these opportunities and grow. Can we finally move forward and skip the explanation, contextualization, and remembrance part and look beyond them, forward? A wish and a question coming from the public. What’s next? As Hafez suggests, if you don’t know the names of ten contemporary Egyptian choreographers, you know where to start with. Then, study well Europe!